Who makes the rules for a Wellbeing Economy?

Table of Contents

This blog post was originally published at the Wellbeing Economy Alliance Website

I would like you to imagine the Wellbeing Economy movement as a two-sided medal. The front side of the medal represents what is most visible about it, such as the participating organizations, their goals, strategies, and research reports. The often-overlooked reverse side represents the people behind the movement, their careers, ideas, and interlinkages. In this blog post, I introduce this reverse side of the Wellbeing Economy movement which I have studied intensively for the last year as a part of my Master’ s Thesis.

My interest in the Wellbeing Economy movement grew steadily during my work at the Happiness Research Institute in Copenhagen and quickly developed into a thesis idea as it resonated well with my education in sociology and international political economy.

In contrast to many political economists who study powerful organizations such as the UN, or countries such as the United States to understand how authority is generated in an international setting, I wanted to understand how people’s backgrounds, strategic positions and professional networks are influencing the success of the Wellbeing Economy movement. Insights into the social relations of active members can provide a different understanding of the movement and shed light on why it is so difficult to “overrule” the current economic system. I very much hope that this sociological view on the Wellbeing Economy movement can give inspiration to new ideas that strengthen the impact of the movement going forward. Intellectually, much of thinking is inspired by scholars at Copenhagen Business school (e.g. Seabrooke & Henriksen, 2017).

Who are members of the Wellbeing Economy Movement? #

In the past year, I collected information on 246 people who actively work on Wellbeing Economy issues in association with the Wellbeing Economy Alliance (WEAll). As with other social movements, membership is fairly heterogeneous, dispersed around the globe and composed of different groups. The movement mainly operates in Europe and other countries from the Global North, while deliberately including underrepresented areas from the Global South (see Table 1).

## Warning: There was 1 warning in `mutate()`.

## ℹ In argument: `across(Country, str_replace_all, "UK", "England (UK)")`.

## Caused by warning:

## ! The `...` argument of `across()` is deprecated as of dplyr 1.1.0.

## Supply arguments directly to `.fns` through an anonymous function instead.

##

## # Previously

## across(a:b, mean, na.rm = TRUE)

##

## # Now

## across(a:b, \(x) mean(x, na.rm = TRUE))

| Country | n |

|---|---|

| England (UK) | 57 |

| United States | 36 |

| Scotland (UK) | 35 |

| Belgium | 15 |

| Finland | 10 |

| Germany | 10 |

| Netherlands | 9 |

| New Zealand | 9 |

| Canada | 8 |

| Australia | 6 |

| France | 6 |

| Costa Rica | 5 |

| Iceland | 5 |

| Sweden | 5 |

| Wales | 5 |

To create an overview, I categorized experts by their sector and professional group (Figure 2). Most of the members are either academics in universities or research institutions. The second largest group is composed of activists who work in NGOs, foundations, and other activist organizations. One fifth of the members work in public or intergovernmental institutions as policymakers, advisers, or politicians, while only a few are businesspeople.

This sectoral distribution of membership tells us about the status of the movement. As relatively few hold positions within the business or policymaking sector – such as national parliaments, administrations or commissions – ideas associated with the Wellbeing Economy are still very distant from the current status quo.

Figure 1: Sectors and professional groups

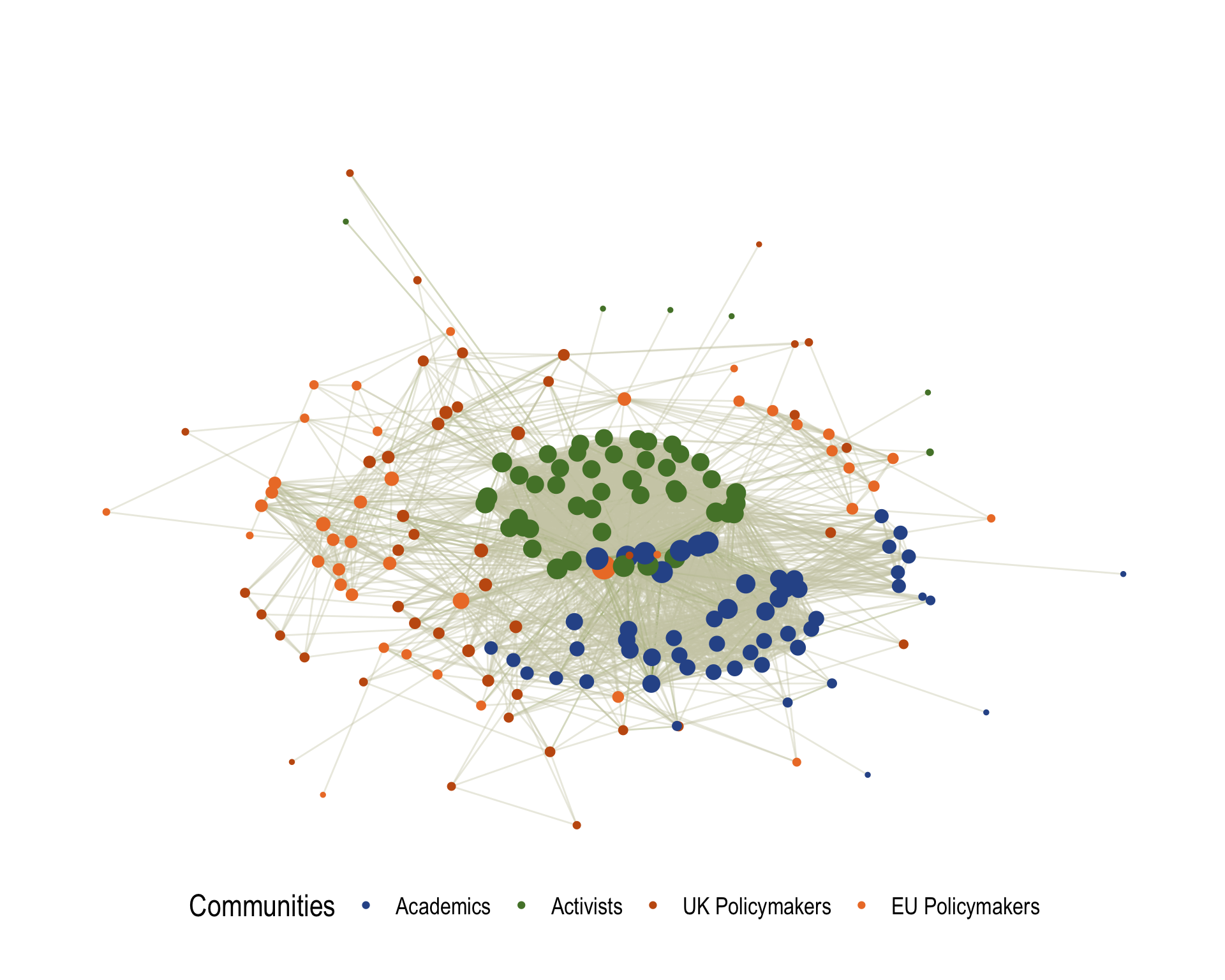

This distance becomes more visible in Figure 3, which shows the professional network of the Wellbeing Economy movement. Each node represents an individual who is connected to other individuals by current or past employment. As highlighted by Louvain’s clustering algorithm, we can see that academics and activists form tighter communities and have stronger organizational affiliations with each other than policymakers. The bigger node sizes of activists and academics also reveal a greater number of organizational overlaps that they have with policymakers. In contrast, EU and UK policymakers form their own, looser communities situated at the periphery of the network.

## Warning: Using the `size` aesthetic in this geom was deprecated in ggplot2 3.4.0.

## ℹ Please use `linewidth` in the `default_aes` field and elsewhere instead.

Figure 2: Professional network of Wellbeing Economy movement

Figure 3: Organizational Network

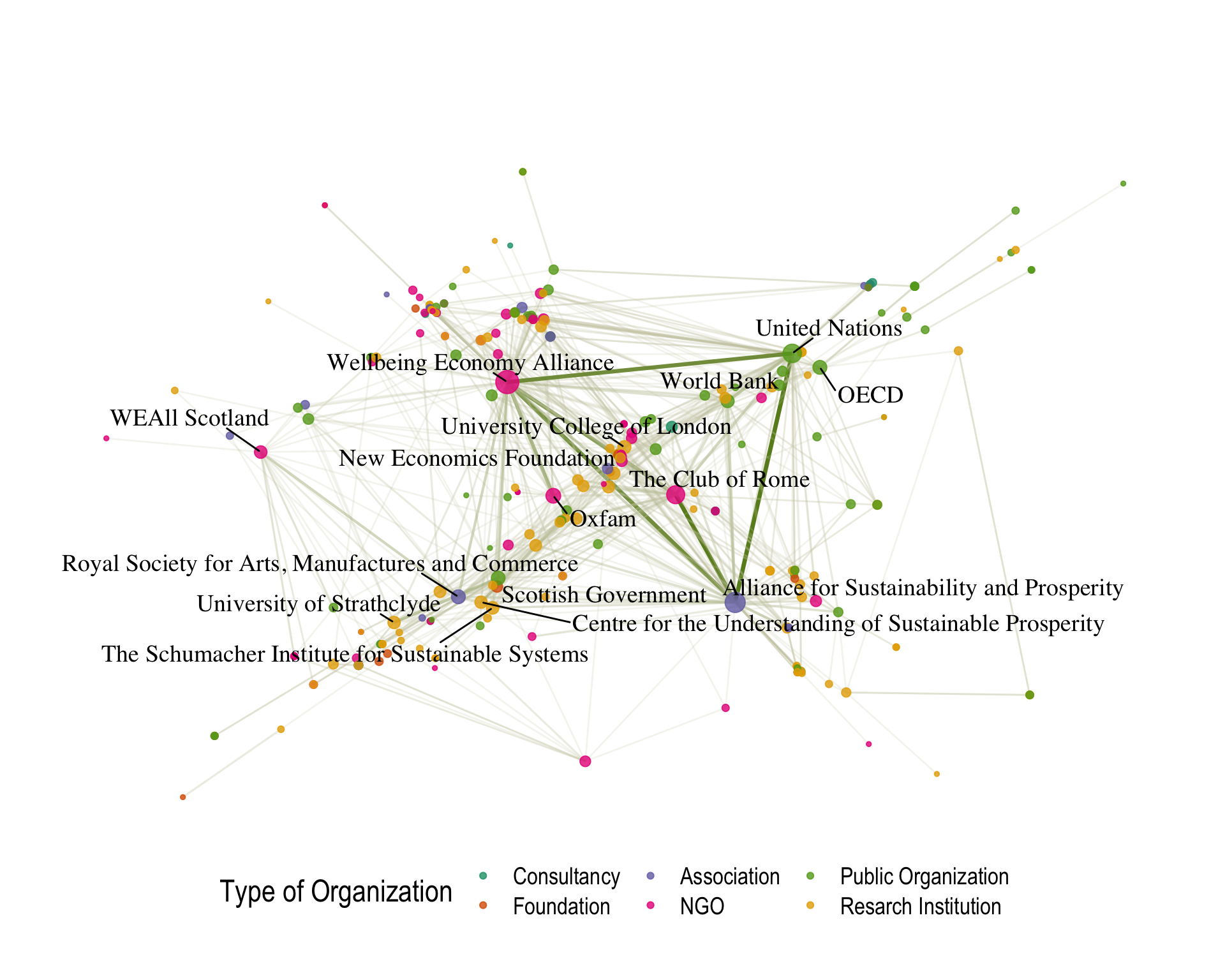

Figure 4 shows the organizational network of the Wellbeing Economy Movement. Organizations with the largest nodes are labeled and weighted according to their number of affiliations; ties are weighted by their shared affiliations. While WEAll and its Scotland hub are among the most prominent organizations by design, other important organizations include international organizations such as the UN, OECD and World Bank, NGOs such as Oxfam and the Club of Rome, as well as a variety of mostly British universities, think tanks and professional organizations. Most noteworthy is the triangular connection between WEAll, the UN and the Alliance for Sustainability and Prosperity, involved in the very creation of WEAll, which is mostly composed of prominent ecological and environmental academics.

In sociological terms, the organizational footprint allows us to identify “locations of change”, where Wellbeing Economy ideas are allowed to prosper. Although international organizations and NGOs are an important ally to have, they alone cannot push for a Wellbeing Economy revolution. The movement strongly relies on the support of prominent national institutions which currently act as gatekeepers for change. Looking back at Figure 4, such national institutions are largely absent in the organizational network of the movement. The Scottish Government is one of the rare exceptions to the case.

What are strategies to achieve a Wellbeing Economy? #

As an umbrella organization, WEAll unites the voices of people and organizations that share the goal to move away from the current growth-seeking economic system. Scholarship on wellbeing policy (e.g. Laurent 2021; Bache & Scott 2018) highlights the existence of three distinct fundamental goals of a Wellbeing Economy, namely: 1) to alleviate social inequalities and poverty, 2) to tackle climate change and other forms of environmental degradation and 3) to increase mental health and subjective wellbeing.

As a result, professional groups possess a variety of strategies aimed at transitioning into a Wellbeing Economy. These include: 1) the measurement and monitoring of wellbeing indicators, 2) the active use of wellbeing indicators in cost-benefit analysis, wellbeing-budgets, or mandated legislation, 3) the explicit use of wellbeing-minded policy, 4) the creation of new socio-political wellbeing narratives, 5) the initiation of system change and 6) an either agnostic, positive or negative stance towards continued economic growth.

Given the recent emergence of the movement, there is currently no unique strategic position on how to transition into a Wellbeing Economy shared amongst all participants. Although some professional groups do possess clear strategic positions, their strategies are mutually conflicting. Figure 5 illustrates that activists and academics advocate for system change while policymakers and other academic groups believe that a Wellbeing Economy is achieved by continuously measuring wellbeing indicators. The conflict is created as the former calls for a radical shift in policymaking, while the latter rather signalizes a reformation of current policymaking through the inclusion – and possibly active use – of wellbeing indicators.

Figure 4: Strategic positions of professional groups

How can we transition into a Wellbeing Economy? #

This quick glimpse at the reverse side of the medal representing the Wellbeing Economy movement reveals the underlying problem and a strategic opportunity. Conflicting strategies between policymakers and other professional groups seem to slow the transformation to a Wellbeing Economy. This is further decelerated by an industry sector that lacks a clear strategic vision towards transformative change.

However, recognizing that strategic positions emerge from current and past forms of social interaction, WEAll has the timely opportunity to change such strategies by building new forms of social interactions between formerly disconnected professional groups.

What the Wellbeing Economy movement has done so far, is to strengthen the strategic coalition between activists and academics – convincing researchers that real, transformative change is necessary. However, coalescing between activists and incumbent policymakers has not yet been successful, partly because transformative change is contrary to the current way of policymaking. One recent exception was seen in Germany, where the Minister of Foreign Affairs appointed Jennifer Morgan, the American head of Greenpeace as a special climate convoy (Schuetze, 2022). More initiatives like this are needed. Thus, to foster the coalition between activists and policymakers from a sociological viewpoint, I have the following recommendations.

My recommendations #

- Foster relationships with policymakers through targeted events, research, or membership involvement. National policymakers are the avenue for change. Change is about creating social ties, and if ties to current and future policymakers can be facilitated, Wellbeing Economy ideas might drive the policymaking of the future.

In the European Union, ideas about the “Economy of Wellbeing” have shown interest from the Council of the European Union (European Council, 2019). In order to convince European policymakers about the Wellbeing Economy, WEAll should:

Focus on policymakers working in national institutions, as they currently only occupy peripheral positions in the network

Consider the strategy: system change through wellbeing measurement – an increasing focus on wellbeing measurement show policymakers the need for system change

References #

Bache, I., & Scott, K. (2018). Wellbeing in Politics and Policy. In I. Bache & K. Scott (Eds.), The Politics of Wellbeing: Theory, Policy and Practice (pp. 1–22). Palgrave Macmillan.

European Council. (2019). Economy of Wellbeing in the EU: People’s Wellbeing Fosters Economic Growth.

Laurent, É. (2021). The Well-being Transition: Analysis and Policy. Palgrave Macmillan.

Christopher F. Schuetze. (2022). Germany Has a New Climate Envoy: an American Greenpeace Activist Link

Seabrooke, L., & Henriksen, L. F. (Eds.). (2017). Professional networks in transnational governance. Cambridge University Press.